Radius of gyration

Radius of gyration or gyradius is the name of several related measures of the size of an object, a surface, or an ensemble of points. It is calculated as the root mean square distance of the objects' parts from either its center of gravity or an axis.

Contents |

Applications in structural engineering

In structural engineering, the two-dimensional radius of gyration is used to describe the distribution of cross sectional area in a column around its centroidal axis. The radius of gyration is given by the following formula

or

where I is the second moment of area and A is the total cross-sectional area. The gyration radius is useful in estimating the stiffness of a column. However, if the principal moments of the two-dimensional gyration tensor are not equal, the column will tend to buckle around the axis with the smaller principal moment. For example, a column with an elliptical cross-section will tend to buckle in the direction of the smaller semiaxis.

It also can be referred to as the radial distance from a given axis at which the mass of a body could be concentrated without altering the rotational inertia of the body about that axis.

In engineering, where people deal with continuous bodies of matter, the radius of gyration is usually calculated as an integral.

Applications in mechanics

The radius of gyration (r) about a given axis can be computed in terms of the mass moment of inertia I around that axis, and the total mass m;

or

I is a scalar, and is not the moment of inertia tensor. [1]

Molecular applications

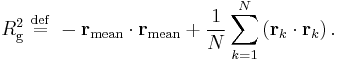

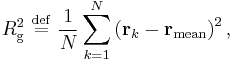

In polymer physics, the radius of gyration is used to describe the dimensions of a polymer chain. The radius of gyration of a particular molecule at a given time is defined as:

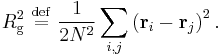

where  is the mean position of the monomers. As detailed below, the radius of gyration is also proportional to the root mean square distance between the monomers:

is the mean position of the monomers. As detailed below, the radius of gyration is also proportional to the root mean square distance between the monomers:

As a third method, the radius of gyration can also be computed by summing the principal moments of the gyration tensor.

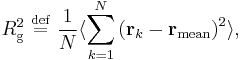

Since the chain conformations of a polymer sample are quasi infinite in number and constantly change over time, the "radius of gyration" discussed in polymer physics must usually be understood as a mean over all polymer molecules of the sample and over time. That is, the radius of gyration which is measured is an average over time or ensemble:

where the angular brackets  denote the ensemble average.

denote the ensemble average.

An entropically governed polymer chain (i.e. in so called theta conditions) follows a random walk in three dimensions. The radius of gyration for this case is given by

Note that although  represents the contour length of the polymer,

represents the contour length of the polymer,  is strongly dependent of polymer stiffness and can vary over orders of magnitude.

is strongly dependent of polymer stiffness and can vary over orders of magnitude.  is reduced accordingly.

is reduced accordingly.

One reason that the radius of gyration is an interesting property is that it can be determined experimentally with static light scattering as well as with small angle neutron- and x-ray scattering. This allows theoretical polymer physicists to check their models against reality. The hydrodynamic radius is numerically similar, and can be measured with Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS).

Derivation of identity

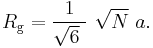

To show that the two definitions of  are identical, we first multiply out the summand in the first definition:

are identical, we first multiply out the summand in the first definition:

Carrying out the summation over the last two terms and using the definition of  gives the formula

gives the formula

Notes

- ^ See for example Goldstein, Herbert (1950), Classical Mechanics (1st ed.), Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company equation 5-30

References

- Grosberg AY and Khokhlov AR. (1994) Statistical Physics of Macromolecules (translated by Atanov YA), AIP Press. ISBN 1563960710

- Flory PJ. (1953) Principles of Polymer Chemistry, Cornell University, pp. 428-429 (Appendix C o Chapter X).

![R_{\mathrm{g}}^{2} \ \stackrel{\mathrm{def}}{=}\

\frac{1}{N} \sum_{k=1}^{N} \left( \mathbf{r}_{k} - \mathbf{r}_{\mathrm{mean}} \right)^{2} =

\frac{1}{N} \sum_{k=1}^{N} \left[ \mathbf{r}_{k} \cdot \mathbf{r}_{k} %2B

\mathbf{r}_{\mathrm{mean}} \cdot \mathbf{r}_{\mathrm{mean}}

- 2 \mathbf{r}_{k} \cdot \mathbf{r}_{\mathrm{mean}} \right].](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/fd995f797783d9f7ada70bfbb7a0a70a.png)